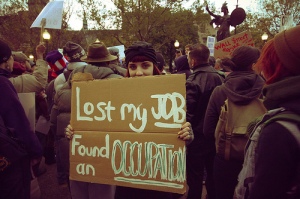

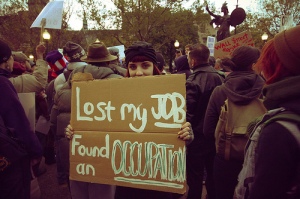

Protesters in Zuccotti Park display their student loan debt in a mock graduation ceremony. Photo by Mark Abramson/The Chronicle.

Despite a hardening contempt among Americans for game show politics and the kind of unrestrained, predatory Wall Street speculation that throttled what was left of our middle class and eviscerated the global economy, it turns out that six months of street theater, Guy Fawkes masks, flash mobs, and finger-waggling hand codes haven’t done much to set things right. Then again, the increasingly evicted Occupy movement has always been more concerned with frustrated privilege and subculturism than radical change.

Granted, there is much to rail against. The statistics have become trite through sloganeering, but they don’t lie. The highest earning 1% of Americans now own 40% of the wealth, while the lowest earning 50% own less than 1%. More than 46 million live in poverty. These people of the abyss, as Jack London called them, slip ever deeper into a state of permanent neglect, a staggering number of them within sight of Capitol Hill, where members of Congress, with a median net worth of just under a million dollars, have done more to speed up the catastrophe than vanquish it.

To deny that the numbers add up to a great inequity is to court iniquity. But what evil has Occupy alleviated, and who are the Occupiers? (“We are the 99%” resonates, but means nothing.) Are they the struggling drudgers, the accidentally, desperately unemployed? Are they swelling with the ranks of those who suffer disproportionately from chronic inequality?

They are not. The surveys and polls agree with the naked eye: the protesters are mostly young, highly educated, at least partly employed, male, and strikingly white. Comparisons to the Civil Rights Movement (protesters sang “We Shall Overcome” while being peaceably evicted from Zuccotti Park) and the Arab Spring are common, and insufferable. It’s true: the Occupiers have been at times inexcusably pepper-sprayed and unduly bullied in the mostly non-violent pursuit of a “world revolution” they can’t define. Demonstrators during the Montgomery Marches and the Tahrir Square uprising had only one demand—the basic human right of enfranchisement—and they made it in the teeth of unrelenting dehumanization, persecution, and murder.

Michael Greenberg, sympathetic chronicler of Occupy Wall Street for the New York Review of Books, notes that the movement, because it embraces “`all people who feel wronged by the corporate forces of the world,’” is “a blank screen on which the grievances of a huge swath of the population can be projected.” (A Time poll from October 2011 showed that 54% of Americans had a favorable opinion of the protests, which were at the time less than a month old. A Pew poll released on December 15 saw that number drop to 44%, with 49% disapproving of the way the protests were being conducted.) But if the airing of genuine grievances is not followed by the formulation, the articulation of actionable solutions, then the sound and the fury—mostly sound, in this case—signifies nothing. This has been the ineradicable criticism of the movement from day one. Protesters told Greenberg last Fall that

… they wished people would stop demanding a demand because the idea of one was of little interest to them… What they cared about was the “process,” a way of thinking and interacting exemplified by their daily General Assembly meetings and the crowded, surprisingly well-mannered village they had created…

And again just after the New Year:

Any… demand would turn them into supplicants; its very utterance implied a surrender to the state that went against Occupy Wall Street’s principles… They saw themselves as a counterculture; and to continue to survive as such they had to remain uncontaminated by the culture they opposed.

This masturbatory mooning over the “process” and the definitive refusal to coalesce (Greenberg’s word), makes Occupy precisely irrelevant, if not profoundly silly, to the slobs outside the bubble who get up every morning to go to work or look for work so the bills get paid and the lights stay on. Activists, as Brendan O’Neill writes, “want to opt out of a society which in their minority middle-class view is too competitive and vulgar and stuff-obsessed,” which is precisely the society the underprivileged have never had the luxury of tasting, much less refusing.

Nevertheless, you will often hear Occupiers proclaim that they are fighting for and represent everyone “without a voice,” a remarkably hideous condescension that smacks of fanaticism. A voice, the power to say “enough,” is all anyone really owns. Those with most to lose tend to guard that power carefully: they know perfectly well when it counts and when it doesn’t. And on those rare occasions when the long-term unemployed, psychologically devastated by being so utterly cut off from the “vile mainstream world” so abhorred by Occupy, do scrape up the time and the money to get to an Occupy General Assembly meeting to plead for some kind of tangible, earthly support, what happens? Why, they are summarily tossed under the wheels of the almighty process, naturally.

***

Even if the movement did focus on a pragmatic core of demands and brace for what Wendy Kaminer called “the hard slog of advancing political and social change,” it would require not just organization, leadership, and diligence, but exclusivity, the expulsion or education of the children who cry for the abolition of the capitalist order and the institution of anarcho-syndicalism. In short, it would mean the end of the Occupy movement.

Photo by Chuck Estin/Inside Bainbridge.

I thought I might be missing something, and I really wanted to get it, so I went to the #OWS website to educate myself. (Revolutions these days have Twitter accounts, and donate buttons, and are designed by “various radicals” on MacBook Pros.) “While cynics demanded we elect leaders and make demands on politicians,” someone writes, though certainly not a leader of any kind, “we were busy creating alternatives to those very institutions. A revolution has been set in motion, and we cannot be stopped.”

Never mind that these alternatives amount to squatting in various public and private-public parks in perpetuity, and that the makeshift campgrounds have since been liberated of protesters, to the great relief of 99% of city dwellers and 100% of squirrels. The direct democracy worked for a while, too, blighted only by occasional bouts of sexual assault, robbery, violence, scarcity, and classism, the legacy of every sizable human community.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, one of many wealthy liberal celebrities belonging to the detested 1% who visited Zuccotti Park last year in support of the movement, said that the protests should be understood as an “expression of frustration with the electoral process,” a wake-up call. It’s all about raising awareness, a phrase that comes up a lot. Elsewhere it’s been called, approvingly, a “carnival,” a “festival,” a “dance,” a “way of being.” Meanwhile, the Tea Party sits down at the table and makes real advances in the consecration of ignorance.

Anyway, it’s unclear to me exactly which Americans are unaware of their foreclosed upon homes, their eliminated pensions, their lingering medical bills and credit card debt, and on and on. A great many are willfully confused as to the causes of their various misfortunes, and blame government largesse or crony capitalism without taking into account moderate to gratuitous personal irresponsibility; but there comes a point at which the unconscious must be disregarded, at least for the time being, for the sake of the living.

Or is it our elected representatives who are unaware that they took an oath to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity”? The U.S. is ranked in the bottom five among 32 advanced and emerging nations when it comes to poverty prevention, overall poverty rate, child poverty, and income inequality. This doesn’t sound very just or tranquil or well-faring, and it didn’t happen overnight.

Any viable “resistance movement” must become aware that a protest is simply a public objection, and that objecting against a thousand evils is objecting against none, and that if the objector, after objecting all day, returns to a tent when he could go home to a heated apartment instead, the act of objecting is primarily cathartic, and the fulfillment of a human need to belong to a tribe. For others, it is even more than that. “I never had many friends growing up,” said one candid young man in a video interview, “and in five days, I have met more best friends here than I have met in 25 years.” Greenberg describes many Occupiers as being “psychologically unable to go about their lives as before.” Gatherings at post-eviction Zuccotti Park have “the aura of a revivalist meeting.”

***

Apart from the rather impressive intelligence, resourcefulness, and hard work that went into organizing, feeding, sheltering, aiding, and otherwise sustaining so many people, most of them genuinely, deeply anxious about the future of this country, I’m sure, what substantive changes has the Occupy movement wrought, and how exactly is it “the most successful American activist movement in decades“? 2011 was “a year in revolt,” the website tells me, and cites “accomplishments” such as:

“We exposed… economic inequality”—i.e. they objected to economic inequality; “We exposed the corruption of money in politics”—i.e. they objected to said corruption; “We contributed to a global movement for economic justice”—i.e. they objected to economic injustice; “We fought for accessible education”—i.e. they objected to inaccessible education while at the same time demanding the immediate cancellation of the student loan debt incurred while receiving the benefits of an education whose inaccessibility they’re objecting to.

They shut down the port of Oakland twice; claimed victory twice. Hundreds or thousands of workers lost wages, including union employees. (Solidarity between organized labor and Occupy has been lukewarm at best and mutually exploitative). Oakland’s mayor, Jean Quan, after entreating the protesters not to disrupt “one of the best sources of good-paying, blue-collar jobs left” in the staunchly blue-collar city, wanted to know “How… shutting down the port and causing thousands of workers to lose a day’s pay [created] positive change?” To date, the city, already on the verge of bankruptcy, has spent at least five million dollars cleaning up after the raising of so much awareness.

Occupy D.C. protesters play Red Rover. Photo by Bill O'Leary/Washington Post.

They’re scoring body blows on the East Coast as well. Occupy D.C. defended its right to monopolize the public square in the name of righteous indignation by staging sleep strikes and erecting a “tent of dreams” over the statue of McPherson Park’s namesake. (Upon hearing of Union General James B. McPherson’s death in the Battle of Atlanta, Ulysses S. Grant is said to have remarked, “The country has lost one of its best soldiers, and I have lost my best friend.”). The collective was eventually expelled by “helmeted and armed mobs” of the infamously brutal National Park Police, although the rat infestation they left behind is thriving. An Occupy Harlem protest (described by the progressive In These Times as “majority-white”) of President Obama at a January 20 Apollo Theater fundraiser was not entirely well received by Harlem residents. One youngster summed up the general sentiment of the neighborhood: “Get the fuck out of my home!”

“We altered mainstream political discourse” is a little more interesting, but just as problematic. On the one hand, “the political establishment tried to co-opt our movement and use our slogans for political gain.” That’s true, but I think they’re saying it’s a bad thing. On the other hand, “Time Magazine named “the protester” its Person of the Year.” I think this is supposed to be the good news. Unfortunately, Time magazine is owned by Time Warner Inc., the largest media conglomerate in the world. CEO Jeff Bewkes, who received a 34% salary increase in 2010, makes a decent $26.3 million a year.

***

In his State of the Union Address, President Obama framed “the defining issue of our time” around the restoration of the “American Promise”:

“We can either settle for a country where a shrinking number of people do really well while a growing number of Americans barely get by, or we can restore an economy where everyone gets a fair shot, and everyone does their fair share, and everyone plays by the same set of rules.”

He said much the same thing in a speech on the economy last December in Kansas, adding that “These aren’t 1% values or 99% values. They’re American values.” So at the very least, the Democrats, with few exceptions a collection of squeaky chew toys badly in need of the votes, will continue to couch their election and reelection bids in a less agitated, more precise, more frivolous version of the language borrowed, or rather co-opted, from Occupy Wall Street; the Republicans will continue to make faces and irritable gestures: they have no light, only Paleolithic terrors of dark, amorous animals circling in the night; and the media will continue to suckle at the necrotic two-party monolith 24 hours a day, seven days a week. This is all it means when commentators and demonstrators remark that Occupy has “changed the conversation.”

What to do, then, as colorful slogans inciting awareness or promising change proliferate on the bumper of a nation that’s stuck in the mud. Over 5000 Occupy protesters have been arrested since the movement’s birthday on September 17, 2011, but not a single person at a major bank has been convicted since the onset of a financial cataclysm ignited, plainly and brazenly, by the incontinent greed of speculators.

The Dodd-Frank Act, which treats some of the symptoms of “too big to fail” but not the disease, has already been targeted for demolition by Wall Street Republicans (the difference between the two bodies no longer demands the separating conjunction). And even if Congress had the audacity to sacrifice itself for the public good by passing real campaign finance reform, the Supreme Court—median net worth: between $2 million and $20 million—has ruled that a ban or limit on corporate campaign spending is a violation of free speech. (Corporations are people too, remember.)

Activism that becomes infatuated with the culture its performance creates is just exhibitionism. It may soothe the frustrations and longings of the performers, but it is not and never will be the solution to a government that no longer stands for the people who do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this country. If we don’t build a true, viable American Left: rational, non-academic, tough-minded, devoid of the tired counterculture rhetoric of the 1960s, and as hell-bent on legislating basic economic fairness as most of Wall Street is on assaulting it—then the hundreds of millions of people who own nothing but a voice are going to decide they’ve had enough, and the rest of us, including the pretend rebels of Occupy, are going to find out the hard way what a real revolution looks like.